The Local Peculiarities of the Development of the Kura-Araxis Culture on the Example of Sakdrisi

The archeological and the interdisciplinary research implemented for years on the territory of Georgia has proved that from the cultural viewpoint this area is the most ancient and it has served as a vector for the creation and development of civilizations. The cultural and social change in the industry and agriculture of the given area started with the introduction of metallurgy. Obtaining and processing as well as the trade of metals led to social differentiation and development of new trade and political relationships.

The first data on the export of the metal from the region are found in Old Assyrian (the marches of Tiglath-Pileser I and Shalmaneser I) and Urartian (marches of Kings Menua, Argishti I and Sardur II to Diauehi and Colchis) sources, as well as numerous Greek references (Strabo, Valerius Flaccus). The ancient Greek authors mention the tribes that produced metal: Chalybes, Mossynoeci, Meskhi, Taochi. It is considered that the Greek name for metal “Chalupsi” (χάλυψ – steel; χάλχος – copper, iron) derived from the toponym denoting Chalybes [Javakhisvili, 1979:23]. The data on Chalybes underlines their special skill of obtaining the desired ore from rivers and producing solid, stainless, shiny weapons from these metals. Their mining capacity is also mentioned in the sources [Giorgadze, 1988:91].

My interest towards the ancient metallurgy is more concrete: the paper aims to study gold, the tribes obtaining gold and their way of life. In this regard, a special study should be made of the ancient Greek literature which makes mention of Colchis and the abundance of gold in this region. Apollonius of Rhodes in his “Argonautica” describes the power of the King of Colchis, his treasures and the Golden Fleece [Apollonius of Rhodes, 1975:117-123]. Apian also speaks of obtaining gold from rivers [Apian, 1959:103]. There are the fragmentary data of the Hellenic period and the Middle Ages on the obtaining of ore. The most detailed data are provided in the 19th century sources in which Russian scientists describe the ancient mines, the lifestyle of the local metallurgists and the efficiency of mines from the prehistoric age to the 19th century. The Russian scientists also research the local and foreign market demand on metals [Абих, 1850:314-324].

In the 19th and 20th centuries, special research was carried out regarding the highland areas of Racha. Over 100 mines were identified and described. The specifics of the mining activities were evaluated and the methods of processing and the efficiency of the ore were assessed. Majority of the above-mentioned mines were actively used in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. The ore was found on the very surface and later, processed and exploited. The first mining method of obtaining ore referred to 80-meters’ adit of Ghula in upper Svaneti, where copper was obtained. All the metallurgical areas, ores, stags, melting furnaces and in some cases, the ceramic material found on the Georgian territory, belong to the epoch, when metallurgy was a leading field of the economy. However, metallic objects dated by the 6th and 5th millennia are found in the burial grounds of Lower Kartli and Trialeti plateau[1]. This proves the existence of the metallurgical spots of much earlier periods.

On the initial stage of development of metallurgy, the mines of the Minor Caucasus and later, Major Caucasus were used. In the Eastern Georgia, Bolnisi region is still an active metallurgical area. The abundance of archeological artefacts and the discovery of the ancient metallurgist settlement gave an impetus to contemporary geological and mining activities implemented in the 80s of the 20th century. The stone sledgehammers and ceramic objects were scattered on the surface. Unfortunately, all the earlier discoveries fell victim to the construction of the present open-cast mine [Mujiri, 1987:53]. In the same period, the archeological study of the region began. A striking novelty was the discovery of the prehistoric gold mine on Kachagiani slope of Sakdrisi mine. Certainly, information on metallic objects is significant, but the discovery of ore-obtaining and processing as well as the settlement of metallurgists is of a special importance.

The contemporary mining archeology embraces the joint research implemented by mining archeologists, mining engineers, geologists and other specialists. Such research will answer the following questions: what was the type of metallurgy in the prehistoric era? Was it restricted to the obtaining of the raw material for the population’s own needs? Was it spontaneous or seasonal? Was it permanent or restricted to a short period? Was it intense? Was it aimed at a large-scale economic turnover? Every researcher of the above-mentioned issues has underlined the natural-technological peculiarities of the mines, their temporal and spatial capacity and the necessity for mining and processing activities [Boyarsky, 1997:8-17]. It has turned out that even in the early period of metallurgy, ore was not obtained without a preliminary testing. If a test did not prove a desired amount of metal in the mine, the metallurgists left the object and started mining in a different place. Near Sakdrisi mine, there were areas for the primary processing. This is an important fact, proving that the prehistoric people did not waste their energy in vain and that they were well aware of ore and selected only profitable objects. All this means that there were professional miners in that period.

Sakdrisi mine. It has been known for a long time that Bolnisi mine has a polymetallic content. It abounds in volcanic sulfides and epithermal deposits of gold and silver, alongside with hematite and quartz [Hauptmann, 2016:27-31].

The archeological study of Sakdrisi-Kachaghiani slope started in 2004-2005. Initially, the archeologists studied the traces of metallurgy of the previous epochs. At first, the issue of gold-mining or the approximate age of the mines was not discussed. The preliminary research proved that quartz deposits of Sakdrisi slope contained gold and the first discovered ceramic material belonged to the Kura-Araxis culture of the 4th -3rd millennia B.C. The materials and artefacts found in Sakdrisi (ore, ceramics, mining tools) proved that the identified mines had been used for centuries, probably seasonally – in late autumn and winter.

During the cleaning of mines, their pockets and entrances, ceramic materials of three historical periods – the Kura-Araxis culture, Hellenic epoch and the Middle Ages – were found. Out of these, 67% belong to the Kura-Araxis culture. According to scholars, the community known under the name of the Kura-Araxis culture dominated over a vast territory for a long period. In the prehistoric era, there were certain reasons for the expansion of cultures, migration and spreading of common features across vast territories. Above all, these reasons imply economic priorities and a desirable ecological as well as geological environment. The culture made significant steps regarding the development of agriculture, cattle-farming, metallurgy and ceramics. All this supported establishing of closer links between the tribes and their interdependence. This interdependence, in its turn, supported common cultural and historical development of South Caucasus and its adjacent areas in the 4th -3rd millennia B.C. That is why the density of population of the South Caucasus was highest in this epoch and the material culture was so unified. Thus, we can argue that the community belonging to the Kura-Araxis culture formed a common spatial-cultural-historical phenomenon [Archeology, 1994:146].

It is still uncertain what tribes formed this culture. There are diverse opinions regarding its constituent tribes (proto-Kartvelian tribes – O. Japaridze, P. Muchaev, G. Melikishvili, T. Gamkrelidze, M. Gajiev and others, Indo-European or Khurite-Urartu tribes) [Alekseev...1989:132-133]. It should be mentioned that the community belonging to the Kura-Araxis culture was, to a certain extent, marginal. At the same time, it had all the preconditions for being transformed into the civilization. However, they failed to make this step and achieve statehood. Besides, it had a well-established elite only in certain areas. Therefore, this progressive cultural community with clear-cut features of an internal local development was not completely adapted. It is considered that the main activities of the tribes belonging to the Kura-Araxis culture were cattle-farming and agriculture [Riotrovsky, 1955:6; Kikvidze, 1975:79]. At the same time, they practised hunting and fishing [Javakhishvili...1965:46]. The development of these two fields must have conditioned the development of crockery and metallurgy. This would lead to the development of narrow trade fields and professional artisans. Craftsmanship implies distribution of labor and development of exchange relationships [Mindiashvili, 1983:195]. This is followed by cultural monopoly over a certain geographical area, where a cultural superiority belongs to a group, which owns technological novelties and the raw materials for which there is a high demand in the given epoch. Probably, metals were the raw materials monopolized by the community during the Kura-Araxis cultural epoch.

Results of the contemporary research. The diversity and amount of stone weapons discovered on Sakdrisi territory points to the gradual stages of the community concentration. Despite being fragmentary, the ceramic material discovered here enables us to make the qualitative and quantitative comparisons between this material and other archeological artefacts discovered on Georgia’s territory, as well as other monuments of the Kura-Araxis culture on the neighboring territories. It would have been hard to analyze the form and function of Sakdrisi ceramics based solely on the artefacts discovered in Sakdrisi. However, the analysis was supported by the artefacts discovered on the ancient settlement of Dzedzvebi, near Balichi village, located at 2 km distance from Sakdrisi. In the so-called “Balichi-Dzedzvebi” settlement, belonging to the Kura-Araxis culture, mining inventory was found alongside with other artefacts. The tools included stone-mills, pressing tools, grinding tools, furnaces and clay crucibles. Two archeological sites turned out to be functionally interrelated: Balichi-Dzedzvebi settlement and Sakdrisi mine must have comprised a unified complex. In order to support this opinion, chemical analysis was carried out, embracing the ceramic material of Sakdrisi, Dzedzvebi and Gudabertka settlement in central Kartli. The analysis was carried out using the X-ray wave fluorescent length (RFA) Pilips PW 2404 equipment. The test enabled research of the micro-elements on the level of one ninth of the atom. Identification and analysis of the key components enables classification of ceramics. It has turned out that the clay of Dzedzvebi-Sakdrisi is characterized by high content of SiO2 and low content of AL2O3 and CaO+MgO. As for Gudabertka material, it abounds in quartz, anorthite and diopside. This proves the geological difference between the raw material used in the above-mentioned places. The ceramics of Sakdrisi and Dzedzvebi are partly similar. The general characteristics is – ceramics poor in calcium. Sakdrisi ceramics were divided into two groups: one of them completely coincides with the ceramics of Balichi-Dzedzvebi, whereas the other has higher content of SiO and lower content of Al2O3. [Otkhvani...2015:9-10]. The coincidence of the content of one group of Sakdrisi ceramics with that of Dzedzvebi settlement proves that the population of Dzedzvebi and the miners of Sakdrisi had common interests. As for the different group, which has low content of MgO and CaO, its discovery near the settlement is a matter of the future, as representatives of the Kura-Araxis culture would not go far for the necessary raw material. In general, ceramics are characterized by traditional, conservative methods which help retain the specific features of the region’s raw materials. Thus, we should suppose that there were local ceramic habits, rules and directions in every open-cast mine [Otchwani, 2012:94-95]. Contemporary potters use local raw material in Sakdrisi-Dzedzvebi and Gudabertka. Thus, we should not exclude the existence of local units within the culture. The Kura-Araxis ceramics are found in Sakdrisi mine on various levels: on the surface debris layers (#10015, 10042, 10042-1, 10101), as well as in the deepest untouched layer (10101-1), dated by the period of development of the Kura-Araxis culture [Stöllner…2011:190-193].

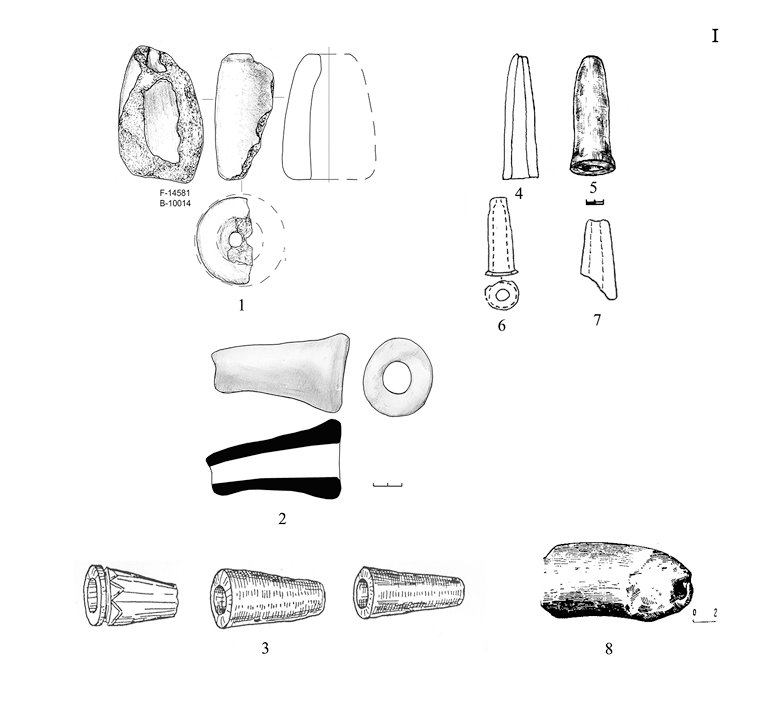

The orifice Pipe. The orifice pipe is a necessary tool for metallurgy. It accelerates melting of ore and regulates the temperature. The conical orifice pipe, made of hard-grained clay, handmade and deficient, was found at entrance A of Sakdrisi mine (picture I, 1). The discovery of such pipe in South Caucasus and Anatolia is the novelty. In Sakdrisi, alongside with stone tools used for breaking the ore, there are pitches for primary processing of the ore, grindstones carved in the rock and the pool also carved in the rock used for washing the ore. The discovery of the orifice pipe continues the logical chain of development of metallurgy.

Picture. I. The orifice pipes from South Caucasus: 1. Sakdrisi mine; 2. Pichori settlement; 3. Ispani settlement (Georgia) 4. Babadervish II 5. Misharchai 6. Yanik Tepe 7. Kul Tepe (Azerbaijan); 8. Jagatsatekh (Armenia).

On the territory of Georgia, the so-called „conical“ orifice pipes with narrow head and wide ending are known from layers VII-VIII of Pichori settlement (picture I. 2), dated by the first half of the 3rd millennium B.C. [Pkhakadze...2008. picture 4-11,12; Pkhakadze, 1993:103-128. picture 25-26.; Jibladze, 2007: 60-75,191. picture CI 8; Ghambashidze... 2010: 489; picture. LIV 872,873]. The discovery made on Amirani hill is of the same period [Chubinishvili, 1971:57-58. XXIV picture 3]. The orifice pipe of Ispani is dated by the second half of the 3rd millennium B.C. (picture I. 3). This pipe is conical, simple, wide at the end, hand-made and hard-burned [Ghambashidze... 2010:486-487. picture # 029-862[121], p.218]. Currently, it is impossible to bring other parallels from Georgia’s territory. As for Azerbaijan and Armenia (picture I. 8), their territories, together with Georgia, formed a unified cultural space of the Kura-Araxis culture. Parallels to Sakdrisi orifice pipe are found in Azerbaijan (picture I, 4-7) on the ancient settlements of Babadervish, Misharchai and Kul Tepe II [Makhmudov, 1968:19], as well as Jagatsatekh settlement in Armenia (picture I, 8) [Ghambashidze...2010:214,229. Picture 034, #61].

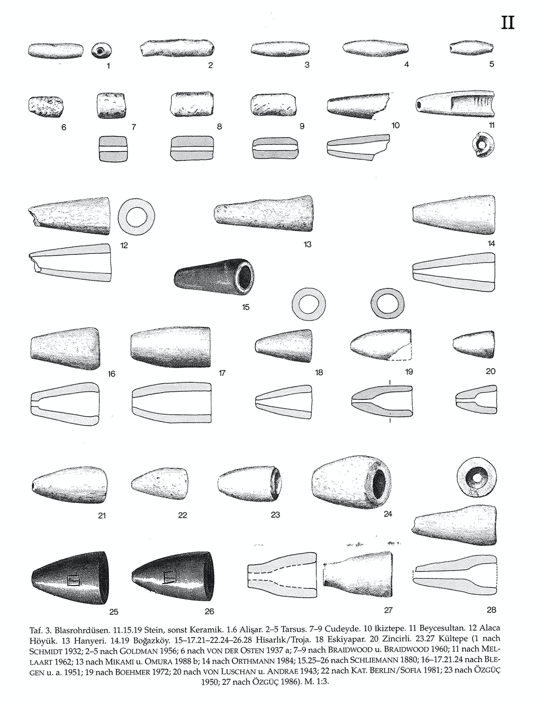

Picture II. Classification of orifice pipes according to Andreas Müller-Karpe.

The first orifice pipes appeared in Anatolia in the first half of the 3rd millennium B.C. In some cases, they were discovered together with molds and other necessary attributes. It should be noted that some of the Anatolian artefacts were either lost or destroyed after World War I. Therefore, we have to rely upon the documents left over by archeologists [Schlimann, 1881:650 #1338]. The earliest sample belongs to Layer XVIII of Beyjesultan; it is dated by the first half of the 3rd millennium B.C. [Efe,1988:117]. The next to come is the orifice pipe found in II layer of Troy, whereas the best fixed in situ object was found on Bogazkoy Bayuk Kale. Later samples were found on Troy layer III and, finally, Troy layer V [Müller-Karpe,1994:189]. The chronological framework of all these artefacts varies from the first half of the 3rd millennium B.C. to the end of the 3rd millennium.

The archeological object of Anatolia, which is most similar to the orifice pipe of Sakdrisi, was found in Troy layer V, construction 50. This sample is infundibular and wider at the sides (picture II, 24-26). There are no other samples of the above-mentioned epoch in Anatolia. In this regard, we could also mention the sample discovered on the Southern terrace of Norshun Tepe [Hauptmann,1982:62].

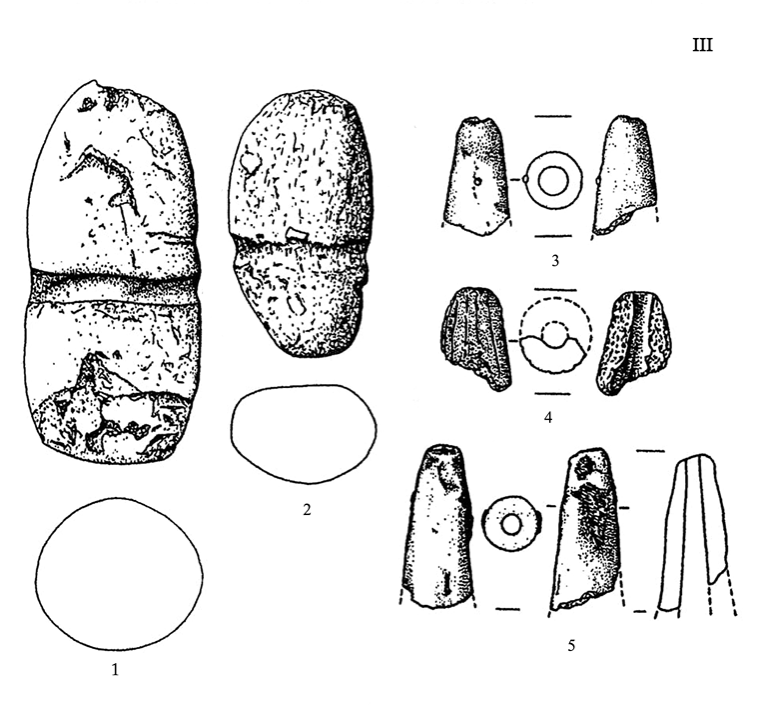

Speaking of foreign parallels, we should mention an exceptional case of finding an orifice pipe in the Alps (Picture III. 3,4,5). Like Sakdrisi, the orifice pipe was found in the Alpine mine, alongside with other objects necessary for mining activities (a sledgehammer, a grindstone, etc.) (Picture III, 1,2). The orifice pipe is dated by the end of the 4th millennium B.C.[2] [Hauptmann, 1982:62].

Picture III. Stone tools and clay orifice pipes from the Bronze Age copper mine (Meerstein, Austria).

In Eastern and Southern Europe, orifice pipes have been found also in burial grounds. First, they were considered as the ends of musical instruments. Later, due to their frequent discovery in mines and ancient settlements, this opinion proved wrong. Burying a deceased person together with orifice pipes must have defined his status. This must have been a widespread ritual at the time.

It is hard to say whether Sakdrisi miners obtained raw material targeted at their own market. The burial grounds found in the ancient settlement of Balichi-Dzedzvebi are not rich in archeological objects. It seems, these objects were made upon order. The micro-elements of gold coils discovered in the burial mound of Hasansu, Azerbaijan, fully coincide with the results of archeometric research of Sakdrisi ore [Stöllner, 2016:105]. This points to the migration of raw materials and development of economic relationships.

[1] As for the objects of the second millennium B.C. found in Trialeti, they represent highly artistic jewellery or military objects, the creation of which requires a special knowledge and a longstanding tradition.

[2] The miners of the Alps were chiefly engaged in obtaining copper

@font-face { font-family: Sylfaen; }@font-face { font-family: "Cambria Math"; }@font-face { font-family: Calibri; }@font-face { font-family: AcadNusx; }p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0cm 0cm 10pt; line-height: 115%; font-size: 11pt; font-family: "Calibri", sans-serif; }p.MsoFootnoteText, li.MsoFootnoteText, div.MsoFootnoteText { margin: 0cm 0cm 0.0001pt; font-size: 10pt; font-family: "Calibri", sans-serif; }span.MsoFootnoteReference { vertical-align: super; }span.FootnoteTextChar { }.MsoChpDefault { font-size: 10pt; font-family: "Calibri", sans-serif; }div.WordSection1 { }

References

| Apian 1959 |

Mithridates Wars. Tbilisi (in Georgian |

| Apollonius of Rhodes 1975 |

Argonautica. Tbilisi (in Georgian). |

| Giorgadze G. 1988 |

The Country of Thousand Deities. Tbilisi (in Georgian). |

| Kikvidze I. 1975 |

Agriculture in Ancient Georgia. Tbilisi (in Georgian). |

| Mindiashvili G. 1983 |

The Study of the Social Structure of the Kura-Araxis Community. Series of History, Archeology, Ethnography and Art History. #1. Tbilisi (in Georgian). |

| Otkhvani N.,Ghambashidze I., Stollner T., Jansen M. 2015 |

Ceramics of the Early Bronze Age from Sakdrisi Mine and Dzedzvebi Settlement Journal of the Georgian National Museum VI (51-B). Tbilisi (in Georgian). |

| Otkhvani N. 2012 |

Characteristics and Diagnostics of Clay as Material for Pottery. Issues of the History and Theory of Culture. XXVII. Tbilisi (in Georgian). |

| Pkhakadze G. 1993 |

The Western Part of South Caucasus in the III Millennium B.C. Tbilisi (in Georgian). |

| Jibladze L. 2007 |

Ancient Settlements of III-II Millenia B.C. on Kolkheti Valley. Tbilisi (in Georgian). |

| Ghambashidze I., Mindiashvili G., Gogochuri G., Kakhiani K., Japaridze I. 2010 |

Ancient Metallurgy and Mining in Georgia in the VI-III Millenia B.C. Tbilisi (in Georgian). |

| Stollner T. 2016 |

The Gold of Sakdrisi. How and in What Amount Was it Obtained? Mining Industry as a Social Process. Sakdrisi Gold – the First Gold Mine in Human History. Bochum. |

| Javakhisivili A. Ghlonti A 1965 |

Urbnisi. Tbilisi. (in Georgian). |

| Javakhisvili I. 1979 |

The History of the Georgian Nation. Tbilisi (in Georgian). |

| Hauptmann A., Jansen M., Stollner T. 2016 |

Sakdrisi Gold – Geology of Ore Deposit. Sakdrisi Gold – the First Gold Mine in Human History. Bochum. |

| Abikh G. 1850 |

Opinions Regarding the Importance of Ore Deposits in South Caucasus. Mining Journal. volume V. Moscow (in Russian). |

| Alekseev V.P. Mkrtchyan R.A. 1989 |

Paleoanthropological Material from the Burial Grounds of Armenia and the Genesis of the Population of the Kura-Araxis Culture. Moscow (in Russian). |

| Archeology 1994 |

Bronze Age in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Moscow. (in Russian). |

| Boyarsky A. 1997 |

The Current State and Objectives of Research of the History of the Native Mining. – in The History of the Science and Technology of Mining. Tbilisi. (in Russian). |

| Makhmudov F.A., Munchaev R.M., Narimanov I.G. 1968 |

On Ancient Metallurgy of the Caucasus, in SA - The Soviet Archeology №4, Moscow (in Russian). |

| Mujiri T. 1987 |

The Influence of Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Monuments of Georgian Mining Industry. Tbilisi (in Russian). |

| Riotrovsky B.B. 1955 |

The Development of Cattle-Farming in Ancient South Caucasus. СА XXIII. Moscow (in Russian). |

| Chubinishvili T.N. 1971 |

On Ancient History of South Caucasus. Tbilisi (in Russian). |

| Efe T. Demirchihüzük. 1988 |

Die Keramik 2 c. Die frühbronzezeitliche Keramik der jüngeren Pfasen - ab Phase H – Ergebnisse Ausgr. 1975-19781 III, 2. Mainz |

| Hauptmann H. 1982 |

Die grabungen auf der Norschuntepe. in Ebd. 1, 7. 1974 Ankara. |

| Huijsman 1. Melita, Krauss Robert # Stibich Robert, 2004 |

Prechistorische Fahlerzbergbau in der Grauwackenzone: In “Anschnit Alpencupfer Rame delle Alpei, Zeitschrift für Kunst und Kultur im Bergbau, Bericht 17, HGW Gerd Weisberger und Gert Goldenberg, Bochum |

| Müller-Karpe 1994 |

Anatolisches Mettalhandwerk, Nevmünster |

| Pkhakadze G., Baramidze M. 2008 |

The Setelment of Pichori and Colchien Bronze Age Chronology. Acient near Erstes Supliment 19, Archaeology in Southern Caukasus:Perspectives From Georgia, Edited bu Antonio Sagona and M. AbramiShvili.Peeters, Leuven-Paris-Dudli, M.A. |

| Roden Ch. 1988 |

Blasrohrdüyen. Ein arxäologischer Exkurs zur PIrotehnologi des Chalkolithikums und der Bronyeyeit. Der Anschnitt 40. |

| Schlimann H., 1881 |

650. # 1338. Ilios. Stadt und land der Tryaner. Forschungen und Entdekungen der Troas und bezonderes auf der Baustelle von Trya, Leipzig |

| Stöllner Thomas & Gambashidze Irina. 2011 |

Gold in Georgia II : The Oldest Gold Mine in the World, in: Anatolian Metal V,Herausgeber:Ünsal Yalçın , Bochum. |